Need for localised management

Common descriptions of the Murray-Darling Basin reference the 2.2 million people who live in the region (MDBA 2022). Yet, within water policy, I believe there is minimal consideration of the role these 2.2 million people could play in successful management of the Basin’s water and reliant ecosystems. Environmental governance, especially water management, is predominately centralised so that decisions and policy development occur within the Federal government (Pittock 2019). Attempts to incorporate local or regional community perspectives tend to be superficial ‘stakeholder engagement’ which is more imparting of information, rather than a genuine incorporation of views (Alexandra 2019; Bischoff-Mattson et al. 2018; Garrick et al. 2012; Pittock 2019). The reality that communities rely on water has, however, driven government agencies to engage at the local scale.

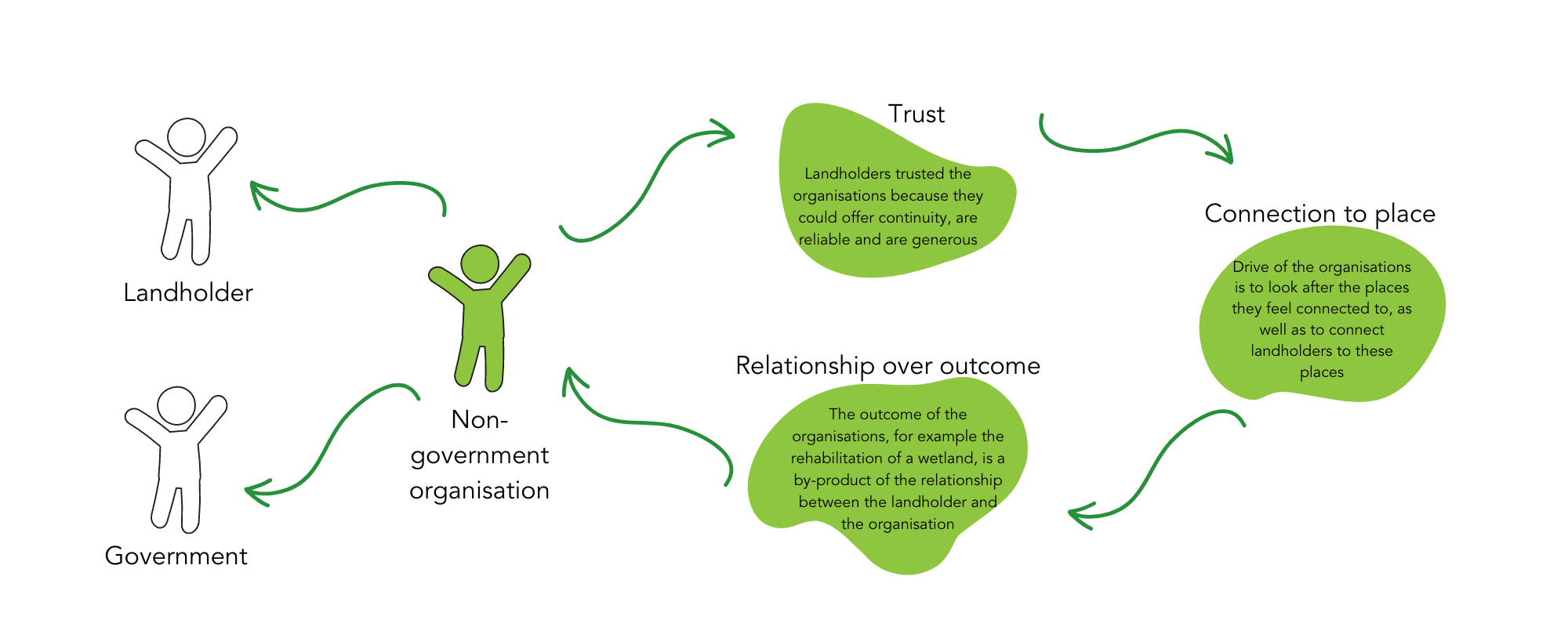

In the context of environmental management beyond state or federal protected areas, a large proportion of water bodies – rivers, wetlands, floodplains, and riverine ecosystems – are on privately owned land. Sometimes there are negative connotations made about private landholders in the Basin (as there also is about government), and these are often exacerbated through publicised mismanagement of a water allocation or environmental flow. The highly contested Basin Plan has, unfortunately, heightened tensions between landholders and government, eroding trust and confidence in processes designed to protect the long-term future of the Murray-Darling Basin (Alexandra 2019; Dare and Lukasiewicz 2019; Garrick et al. 2012).

For the NGOs I interviewed, and based on my personal experience, landholders are deeply familiar with the land they are on, and in most instances are motivated and passionate about protecting their home. It is beginning to be recognised that decisions in environment and water management would greatly benefit from more local involvement, and that there is a need for more collaborative relationships between government and local/regional communities. The call for ‘localism’ or various connected ideas like subsidiarity and collaborative governance, is gaining momentum as a key approach for environmental management (Alexandra 2019; Dare and Lukasiewicz 2019; Garrick et al. 2012; Pittock 2019; Robinson et al. 2015; Tan 2012). It is where local perspectives are understood and integrated into management – either through delegation of management to the scale appropriate (i.e. away from centralised government) and/or through more genuine collaboration (Robinson et al. 2015).

The eight NGOs I interviewed provided a window into why local scale management is crucial for the overall success of environmental management. Each organisation collaborates with landholders to achieve on-ground change at landscape and river reach scale.

Written by Isobel Bender

Written by Isobel Bender